|

Summary The municipality of De Bilt is nine centuries old. Its six villages were built on grounds which could never be inhabited nine centuries ago, because they were all moors. But in the twelfth and thirteenth century, these grounds were cultivated by the monks of the St. Lawrence Abbey, founded at Oostbroek, east of Utrecht. How it started Around 1113, a knight from this area made a pilgrimage to St. Patrick's Purgatory, in the North Western part of Ireland, on an island in Lough Derg (now Co. Donegal) - as did many knights in those days, in order to be purged from bloodshed and other sins. After his pilgrimage, he came back and formed a group of hermits, men and women, who retreated into the moors of Oostbroek. There, according to the chronicles of the medieval historian Hendrik of Thabor, he helped the bishop Godebald build a church.(for the picture: see Chronicles) |

This knight was also mentioned in 1125 by Godebald (bishop 1114-1127), who wrote that some knights, among whom Hermannus and Theodoricus, had chosen better lives as monks in the moors of Oostbroek and founded there a church to the honour of the holy Mary and of St. Lawrence. Before that, in 1122, the empress Mathilde donated all the surrounding lands to 'the young monastery, founded by some converted knights'. Her charter ended with 'In Dei nomine feliciter' (in God's name blessed), the device of St. Willibrord, who had brought the faith from Ireland to the Netherlands, four centuries earlier. The building of the church at Oostbroek must have started as soon as Godebald became bishop of Utrecht (in 1114), shortly after the pilgrim's return from Ireland; because some three years later, the community had already grown big enough to welcome its first abbot, Ludolfus from Brugge; he had led the priory of St. Andrew there since 1100, and (as his successor is recorded in 1118) he must have arrived here around 1117. He came with his half sister, who probably was to lead the women's convent. The buildings would have been ready in 1121, because another medieval historian, Jan Beke, has this as the founding year of the St. Lawrence Abbey; and in the later nunnery, a wall inscription has been found honouring Godebald as their founding bishop anno 1121. |

|

| Highcross in Moone, Ierland - very old, last half of 7th century |

|

Double house split up Probably in 1123, abbot Ludolf decided that the number of women was too much for this monastery, so the women were now to have their own house: a nunnery to be built a mile nearer to Utrecht, on more sandy grounds that had been used as a provisory place to live during the building period at Oostbroek; the new nunnery was finished and officially opened in 1139 (according to the chronicles of a later abbess, Henrica van Erp). Ludolf's document is lost; a copy (from 1231, partially a falsification, adding restrictions for the women) is dated 1113. But this is hardly possible, as Godebald started as bishop in 1114; so this year mcxiii must have been miscopied, likely from mcxxiii (with the omission of an x). 1123 as the year to split up is plausible, for in 1121 the buildings were ready and the monastery was opened; then the young abbey was recognized by the empress in 1122, which made its name well known; and in the same year Godebald succeeded to place a dam in the Curved Rhine, which stopped the continuous flooding of the moorlands around Oostbroek, so that the moors could now be cultivated at a larger scale, which also will have made the community grow. Matilda and Willibrord Not only the empress (Maud or Matilda of England, 1102-67) honoured Willibrord as the apostle of the Low Lands, by quoting his device; also in the St. Lawrence abbey his name was held high. In a necrology of Oostbroek, which was found back two centuries ago, the dates of remembrance of the founders are listed (their deaths seen as their births in heaven): Hermannus and Theodoricus, Godebaldus and Ludolfus. On each date, a vigil should be held in the chapel and a hymn of St Willibrord should be sung. Another connection between Mathilde and Willibrord is to be found in the Louvre, Paris: a portable cross showing the risen Christ blessing king Oswald, who introduced Christianity into Northumbria by inviting a missionary from the monastery of Iona to his country, in 635. St. Aidan, working from Lindisfarne, founded churches and monasteries in Oswald's lands, one of them in Ripon. Willibrord, born in 658, grew up in Ripon, studied in Ireland (Rath Melsigi, now Clonmelsh near Carlow) from 678-690, then pilgrimaged to the Low Lands and became the apostle of the Dutch. In his Calendar, he recommends the veneration of Irish saints like Patrick and Brigid, and of English saints like Oswald. This Oswald appears on a fine cross (now in the Louvre; for the picture: see Willibrord, at the bottom of the article) that was given to Mathilde's granddaughter (who was also called Mathilde) at her wedding in 1168 with the Henry the Lion, duke of Saxony. In those days, the English king (Henry II, Mathilde's son) remained loyal to Rome, while the German emperor had broken up with the pope; which was precisely the reason why the old empress was worried. Believing this Henry the Lion took sides with his emperor, in 1165, when this marriage was to be negotiated at her house in Rouen, she firmly refused to receive anyone from Saxony. She did not live to be at the wedding (she died 1167), so this present will have been given by her son. But it made clear what the empress stood for, and what tradition was hereby handed over. The message must have struck home, for the information centre of Dover Castle shows Henry the Lion as a pilgrim to Thomas Becket's shrine, being in exile. When he did not support his emperor in his war against Lombardy (and the emperor lost), he was driven out of Germany. By taking sides with his English family, he joined the tradition of St. Oswald, advocated by St. Willibrord and by his grandmother-in-law. An early source about the Purgatory The pilgrims who went to the Purgatory are listed in Michael Haren & Yolande de Pontfarcy, The Medieval Pilgrimage to St. Patrick's Purgatory (1988). The list starts with an Irish knight, Owein, who went into the cave around 1147. Eventually, his tale was written down by Henry of Saltrey, around 1185. This Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii became very popular, was translated in most European languages, and attracted many pilgrims from all over the Continent, most of them in the 14th and 15th century. Our knight, however, precedes even knight Owein. So he must have heard about the Purgatory from another source. In Haren and De Pontfarcy's collection (p. 59 note 4) this other source is only briefly mentioned. Having learned about Hendrik of Thabor's chronicles and accepting the knight from Holland as a historical figure, dr. Haren decided to dig further. He found out that the emperor Henry V and his wife Matilda had in their retinue an Irish chaplain, David of Würzburg, who was appointed as chronicler for the imperial campaigns into Italy (1110-11 and 1116-17). Of all his previous writings, the reason for his appointment must have been his De Purgatorio Patricii. Shortly before the first campaign, at Easter 1110, Henry and Matilda were betrothed in the church of Utrecht. David of Würzburg will have been there, too, so probably from that year on the news about the Purgatory spread in the area of Utrecht and inspired a knight here to go on a pilgrimage to Ireland. Returning, he helped the bishop build a church, at the earliest from 1114 on, so the pilgrimage may have taken place in 1113. Celtic spirituality What the knight (Herman or Theoderic) brought back from his Irish pilgrimage was the spirituality of St. Patrick's Purgatory and of the Irish monasteries he visited on his journey to Lough Derg; but it did not start there. He must have heard about the Celtic way before he went. The mere fact of such a pilgrimage suggests that the people in these Low Lands still knew where their apostle Willibrord came from. The Irish-Celtic inspiration must have been of some influence here before Theoderic's pilgrimage; but certainly his journey will have enforced this influence. So, what was kept alive in Oostbroek for centuries, together with Willibrord's veneration, was the Celtic monastic tradition of working hard (in this case, in the moors), reading the Bible and praying the psalms of David, and caring for the sick and the poor. Godebald's text of 1125 allowed the abbot to have certain possessions, in order to guarantee charity and hospitality to poor persons. And in 1131, a document by the next bishop already mentioned the infirmary of the abbey. The Irish influence appears to have lasted as long as the abbey existed. We can see this in a place named after Oostbroek, at the other end of its region: Westbroek. Here, a church was built between 1467 and 1481. In 1510, wall paintings were added. Besides a large picture of the Last Judgment and a scene with three dead men telling three living men a moral lesson, we see six saints, chosen by the abbot of Oostbroek. St. Lawrence, the patron saint of the abbey, is flanked by two Irish companions of St. Willibrord, St. Werenfried and St. Engelmond. And among the female saints is St. Brigid of Ireland (who was also mentioned by St. Willibrord on his Calendar). The fact that three out of six pictured saints are Irish, means that four centuries later, the St. Lawrence abbey still saw itself standing in the monastic tradition from Ireland. |

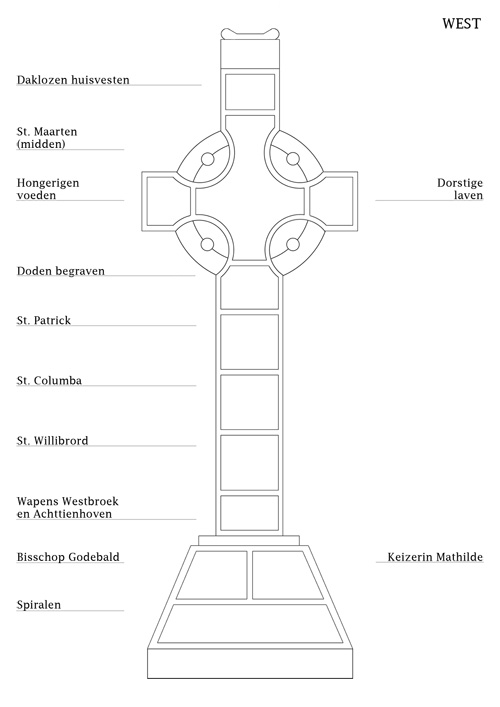

High Crosses On his Irish journey, the pilgrim knight must have seen many examples of this monastic life, and also - on each abbey site he visited - an Irish High Cross. For instance the famous High Crosses of Monasterboice, which are hard to be missed when you travel from the port of Drogheda to the Purgatory in Lough Derg. Even in the days of Willibrord, High Crosses already have been sculptured: for instance at Ahenny and Moone, South West of Dublin, not far from Clonmelsh where Willibrord has been studying. Those early crosses may even have been seen by our apostle before he came to our lands. Such Crosses mirror the spirituality of early Christianity: the love of God and his creation, expressed by animal and plant carvings, and by the spirals and the Celtic knots with their interwoven lines; the victory of Christ over sin and death; examples of Christian life, serving and loving one another, role models from the Bible and the history of the Church. A High Cross in De Bilt Because the municipality of De Bilt has Irish roots, in September 2013, these origins have taken shape here. A young local sculpture, commissioned to make a Celtic High Cross, has travelled to Lough Derg and seen the most important High Crosses of Ireland, to get his ideas. What he now has sculptured is the first figure High Cross on the Continent! As every Celtic Cross, this High Cross has a circle connecting its four arms. On the sides, it has many Celtic knots and spirals and other nature forms. On the front, it shows a line of saints: from Lawrence, Martin, Patrick, Columba of Iona, down to Willibrord. Around the base, those in our local history who were inspired by them: the pilgrim knight, the bishop, the empress, the abbot and later abbess. From the Bible it has Adam and Eve, David playing the harp and singing psalms, and Mary (the St. Lawrence Abbey was also dedicated to St. Mary) with her baby, visited by all mankind in the shape of the three Wise Men - and a fourth figure, representing all spectators, looking over their shoulders (as the Cross of Monasterboice has it). The coiled snakes (circle east side) are taken from the ancient Moone cross, probably also seen by St. Willibrord during his study nearby. St. Martin is central, in the circle (west side), surrounded by the works of charity as we find them in Matthew 25: apart from clothing the naked (what we see St. Martin doing), feeding the hungry, letting the thirsty drink, housing the homeless, visiting those in prison, and caring for the sick. Also burying the dead, added in the Middle Ages as the seventh work of charity, appears on this cross. With all these pictures, this High Cross is meant to make the Celtic spirituality of our founders visible to 21st century spectators. And because one of our villages is called Martin's Dyke, St. Martin is shown riding in that direction (just as the knight rides in the direction of Ireland). The abbot and abbess look towards where their monasteries once stood, and Godebald looks towards Utrecht. Further, the logos of our villages are to be seen on the cross.

Detailed design West On this website The link 'Het kruis' (the Cross) will take you to the figures that have been sculptured. Each figure is briefly explained (in Dutch). |